|

Marvel's new MOKF lacks punch of its predecessor

review by Mike Baron When the kung fu craze hit in the seventies, Marvel was quick to capitalize with Master of Kung Fu. Version 1, by Steve Englehart and Jim Starlin, was thoughtful and solid, backed by Englehart's heart-felt mysticism and Starlin's dynamic pencils. Readers can be forgiven if they think Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy created the franchise, since it is their version that remains indelible in the collective memory. Gulacy's progress as penciller was as astounding in its own way as Barry Windsor-Smith's on Conan the Barbarian.

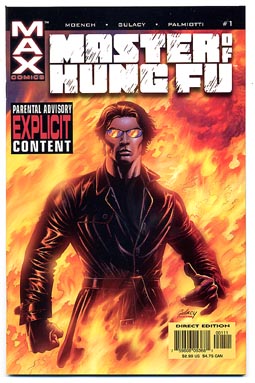

Master of Kung Fu 1 © 2002, Marvel Comics Gulacy's early issues were strongly influenced by Steranko, if a little clunky. Then something happened. Paul took a break and came back, with MOKF #23. Readers were gob-smacked. It was as if he'd climbed a mountain in Nepal, in the interim, and learned the secret of the magic eye-slash. With #29, which he inked himself, the transformation was complete. Gulacy's cinematic, graphic style derived from Steranko had gone beyond the master. His images pulsed with life and menace, and the fact that he used photo ref for Clive Reston and Shang Chi only added to the impact. Some guys use photo ref and it looks like a bad copy. Gulacy used photo ref as homage and collage. Never have comics seemed so cinematic. The kung fu, unfortunately, was nothing to write home about. You'd think a comic patterned after a martial art would make some use of the fact. Even the so-so chop sockey's are crammed with brilliant fight choreography and near super-human stunts. Kung fu movies were created in the East for martial arts aficionados. The Chinese audience is highly knowledgeable about martial arts, and can quickly discern between fakes and the real thing. That's why they made Bruce Lee an overnight sensation, in turn giving rise to the kung fu craze that created MOKF. Doug Moench is a solid professional with a credit list longer than Massachusetts Avenue. At one point he was writing all three Batman titles. He and Gulacy agreed that MOKF was their take on James Bond. The Man With The Golden Gun became the Lazarus adventure. Moench's writing was a little prolix and self-conscious, but the pictures more than made up for it, at least for young fans in love with the medium. Moench/Gulacy went on to produce many other comics, including some Batman and James Bond himself. Now, after years in the wilderness, MOKF is back. Sadly, the kung fu still ain't much to write home about. Nor is the story. The pictures are pretty, but there is no sense of motion, certainly no sense that these guys know anything about martial arts. So what, you ask? So why build your house on the foundation of a visually and viscerally exciting martial art without drawing on kung fu's rich tradition? Max Comics MOKF #1 follows the It's Only A Comic tradition. But comics are what you make of them. They can be slight and shallow, or they can be deep and engrossing, as Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and John Ostrander have demonstrated. The story concerns the return of Comte de Saint Germain, an eighteenth century adventurer know "Der Wundermann" who allegedly lived for centuries. Moench has a knack for resurrecting oddball characters from history, but the story, such a it is, consists of a good deal of close-ups of furious action and little exposition. The whole thing could have been condensed into half the space. Gulacy's chops, aided by state of the art coloring and Jimmy Palmiotti's flawless inking, are strong as ever, but he's abandoned the photo ref in favor of his own style, perfectly serviceable, but lacking in the character of his previous outstanding work. In a chop-sockey, the first action sequence sets the stage. Think of Bruce Lee beating on Sammo Hung in Enter The Dragon, or any Steven Seagal movie. The opening sequence in MOKF #1 involves Leiko Wu beating back a horde of assassins. Gulacy trades clarity for close-ups. She's holding a gun, but the first good look at it comes when someone whacks her in the hand and she drops it. This is a close-up. Leiko uses her left hand to block the next blow, then somehow gets her hand around the assailant's arm, to the other side. This is an impossible technique in real life, although there is logic to the two next moves. Then it's bodies flying through the air and artful kicks, but we never see how she got there. It's so easy to show technique in graphic form, one wonders why the creators do not avail themselves of the opportunity. By simply holding the camera steady and allowing the hero to go through her moves, step-by-step, comics can impart a true sense of motion. Check out Chuck Dixon's and Val Mayerik's The Young Master. Any issue will do, but YM #4 has particularly eloquent sequence on pages nine and ten which show what skilled artists can do to impart motion to the page. Val Mayerik is, of course, an accomplished martial artist, but I've seen the same effect accomplished by other artists who are not, simply by using photo reference. Martial arts manuals and magazines are filled with step-by-step photo how-to articles, the raw material from which many a masterful movie sequence has been made. Some of the story-telling decisions make no sense, like the huge panel devoted to Leiko Wu sitting on the ground clutching her head. For this they needed three quarters of a page? The splash page is beautiful, indulging Gulacy's enthusiasm for Eastern art. But Shang Chi seems to have lost his distinctive looks. This new Shang Chi is generic, and doesn't seem very Chinese. Black Jack Tarr has undergone a metamorphosis from square-jawed Black Irish to spade-jawed esthete. The cover does not play to Gulacy's strengths. Compare the cover of MOKF #1 to the cover of Comic Book Artist #7 which Gulacy also drew, and also features Shang Chi. MOKF was a long time coming, but it's thin gruel. Mike Baron is the creator of the award winning comic book Nexus and during his career has written an enormous variety of comics from The Flash to The Punisher. Visit our Comic Book News Archive. |